How Warren Buffett invests

My understanding of how Buffett approaches investing, including the structural advantages that he’s assembled over time

Investing is making financial bets on future states of the world. You either make or lose money depending on (1) how much you had at stake, and (2) how the world has turned out to be vs what you had predicted.

If investing is betting, investing successfully over the long term requires an edge. Without some sort of advantage on your side, your bets will, almost inevitably, end with ruin.

Strategies for finding and exploiting edges abound. I am most familiar with Warren Buffett’s approach, and here’s how I would distill it today (in February 2021).

An asset should pay for itself

First and foremost, whenever buying a financial asset, Buffett seeks to make money from cash flows produced by the assets themselves — and not from a future sale at a higher (than initially bought at) price.

Why does he rely on asset-produced cash flows rather than on asset sales for increasing wealth?

That is because Buffett claims no insight about where stock prices are going to be in the near future. Over his lifetime the market has had both unreasonably euphoric times and highly pessimistic periods. Having no insight on short-term movements of market prices, he makes a conscious and deliberate effort to be “independent” from them.

This attitude is in stark contrast to how most people approach investing. Most people are trying to “buy low” and “sell high,” but what Buffett does is different. Unsurprisingly, he does aim to “buy low.” But because he wants the asset to pay itself, selling (high or not) isn’t as important to him as it is for most people.

There is also at least one benefit in being less reliant on a future sale. It greatly reduces the chances of he being in the position of needing to sell an asset at a potentially unfavorable price.

As much as he avoids being on the spot to sell, risk is not completely gone. In fact, one could say that Buffett “remolds” the risk he takes. His approach is to protect oneself from the negative impact of not finding prospective buyers who will be willing to buy an asset at a higher price. Nevertheless, the risk of not earning a good return because the asset produced underwhelming cash flows is still very much present in his bets.

Predict the future in specific circumstances

Buffett is, of course, aware of the risk of future cash flows not coming in as expected. He works to minimize this risk by applying the following tenet:

For businesses in some specific circumstances, Buffett is extremely confident that he can predict, with a rough precision, the business owner’s earnings 10+ years out in the future.

In other words, because Buffett doesn’t know much about where the market is going, he aims to make money independently of future prices of assets he owns. And the way he does that is by buying specific businesses whenever their prices seem attractive vs their ability of generating future cash flows (as estimated by Buffett).

In many ways, this is just being conservative and applying common sense. Again, if you want to make money while not depending on the capricious stock market, then the investment itself must pay you back in form of profits.

It is as if Buffett claimed to know nearly nothing about overall market prices in the near future, but a lot about earnings of certain businesses decades ahead.

In his own words (sidenote: Almost all of Buffett’s remarks that we quote in this essay come his Q&A sessions at Berkshire Hathaway’s Annual Shareholder Meetings and his Annual Letters to Berkshire Shareholders over the years.

In order to maintain the narrative flow of the excerpts, omissions and minor edits are not always explicitly indicated.

I kept all of Buffett’s emphasis in writing. In a few excerpts, I did add my own emphasis and annotations.) :

If somebody gave me all 500 stocks in the S&P and I had to make some prediction about how they would behave relative to the market over the next couple years, I don’t know how I would do. But maybe I can find one in there where I think I’m 90% in being right

WB: If somebody gave me all 500 stocks in the S&P and I had to make some prediction about how they would behave relative to the market over the next couple years, I don’t know how I would do. But maybe I can find one in there where I think I’m 90% in being right.

This is an enormous advantage in stocks. You only have to be right on the very, very few things in your lifetime as long as you never make any big mistakes.

WB: As a practical matter, there’s just some businesses that possess economic characteristics that make their future prospects far out far more predictable than others. There are all kinds of businesses that you just can’t remotely predict what they’ll earn, and you just have to forget about them.

Warren Buffett, 2003 Annual Meeting

Make the future more amenable to predictions

But can he really predict the future cash flows of the kinds of businesses he buys?

The world is ever changing. How on earth can anyone predict decades ahead? And do that consistently — even if for just a few stocks?

If we take Buffett’s astonishing track record as evidence, it does seem he is doing something right. I’d submit that there are indeed tricks that Buffett employs to make predicting the future somewhat viable.

Chiefly, he is very picky about the specific circumstances surrounding the businesses he considers investing in.

What does Buffett have in mind when selecting investment candidates? An asset must pass some filters. The key ones are:

A business

Buffett strongly prefers to invest in businesses. He buys either a portion (via the stock market) or 100% of businesses. For the most part, he shies away from gold because it is not a cash generating asset (same for other commodities). He finds real estate too hard to find mispriced opportunities and avoid it as well. The exception to business is bonds. Eventually, he takes advantage of large price dislocations in bonds, but most of the time he is out of the fixed income market.Businesses ran by competent and honest people

Buffett is admittedly a hands-off manager. In Berkshire he does capital allocation and that’s pretty much it. So, when buying an entire businesses, Buffett seeks to keep the current management in place. And when investing in the public markets, he says he looks for candid and capable management. In either case, he needs to trust the management because, again, predicting the future is hard enough. Dealing with incompetent or mischievous people would make the future either downright bad or at least harder to predict. Ideally, Buffett looks for managers who are independently wealthy (and therefore didn’t need to be there working), but who deliberately chose to continue running the business because there is nothing else they would rather do.Businesses with deep, wide economic moats

Economic moats mean durable competitive advantages. Buffett looks for them because they make forecasting easier. It is a trick to be more confident in extrapolating the present into the future with less chance of being too optimistic. In other words, if a business has an enduring moat, Buffett is more confident this business’ competitive dynamics are going to stay largely the same and earnings over decades will be less affected by competition. Moats are key to the whole issue of predictability.

Buffett has written that Berkshire Hathaway looks for well-run and sensibly-priced business with fine economics

(sidenote: 1997 Annual Letter.) . We will get to the question of sensible prices soon. For now, simply note that his choice of words maps very well to our list of filters: business, well-run, and fine economics. That is no coincidence, of course.

His third filter, the existence of economic moats (or fine economics), has important nuances to it. So let’s dig a bit deeper.

Buffett has a famous analogy that likens businesses to castles whose defenses are “economic moats”:

Millions of people are out there with capital thinking about ways to take your castle away from you, and appropriate it for their own use. And then the question is, what kind of a moat do you have around that castle that protects it?

WB: Every business that we look at we think of as an economic castle. And castles are subject to marauders.

The menace of marauders also happens in capitalism — with any castle that you might have, whether it’s razor blades, or soft drinks, or whatever. And you want the capitalistic system to work this way. Millions of people are out there with capital thinking about ways to take your castle away from you, and appropriate it for their own use.

And then the question is, what kind of a moat do you have around that castle that protects it?

Warren Buffett, 2000 Annual Meeting

In practice, a key requirement behind a strong “economic moat” are industry dynamics that are unlikely to change:

When we generally look at businesses, we feel change is likely to work against us. We do not think we have great ability to predict where change is going to lead

WB: When we generally look at businesses, we feel change is likely to work against us. We do not think we have great ability to predict where change is going to lead.

We think we have some ability to find businesses where we don’t think change is going to be very important. We think we know, in a general way, what the soft drink industry or the shaving industry or the candy business is going to look like 10 or 20 years from now.

We think Microsoft is a sensational company run by the best of managers. But we don’t have any idea what that world is going to look like in 10 or 20 years [in software and technology].

If somebody tells us the business is going to change a lot, we don’t think it’s an opportunity at all. I mean, it scares the hell out of us. Because we don’t know how things are going to change.

You know, when people are chewing a chewing gum, we have a pretty good idea how they chewed it 20 years ago and how they’ll chew it 20 years from now. And we don’t really see a lot of technology going into the art of the chew, you know?

And as long as we don’t have to make those other decisions, why in the world should we? I mean, there are all kinds of things that we don’t know. And so, why going around trying to bet on things we don’t know, when we can bet on the simple things?

Warren Buffett, 1996 Annual Meeting

Incidentally, Buffett often says that he only invests in businesses that he understands. People confuse what he means by “understanding a business”, though. To him, understanding is being able to predict, with high confidence, that the uses and capital profile of a business won’t get worse over the next, say, 10 years.

Another popular misinterpretation in the 1990 and early 2000s is that Buffett did not “understand” tech businesses. His old age and the fact that he did not invest in tech companies (up until recently) have led people to believe that. But that could not be further from the truth. Buffett has spent a great number of hours with Bill Gates since the early 1990s. They surely discussed business matters in depth. Buffett also knew the founders of Intel since the company’s early days in the 1970s (sidenote: Alice Schroeder, Buffett’s biographer, writes about his close friendships with Bill Gates and Andy Grove in her book The Snowball.) .

It was not lack of familiarity with tech businesses that kept Buffett away from “tech,” it was something else. Buffett simply could not place a bet on these companies because their industries have been in a constant state of flux. He simply could not predict with high confidence their future 10 years ahead because they change too much.

I should emphasize that, as citizens, Charlie (sidenote: In his famous 1994 commencement speech at USC, Munger said that:

“Warren and I don’t feel like we have any great advantage in the high-tech sector. In fact, we feel like we’re at a big disadvantage in trying to understand the nature of technical developments in software, computer chips or what have you. So we tend to avoid that stuff.”) and I welcome change: fresh ideas, new products, innovative processes and the like cause our country’s standard of living to rise, and that’s clearly good. As investors, however, our reaction to a fermenting industry is much like our attitude toward space exploration: we applaud the endeavor but prefer to skip the ride.

Warren Buffett, 1996 Annual Letter

Design structural advantages

Buffett’s advantages in investing stem not only from being able to predict the future of some businesses in some specific circumstances. He thinks deeply about risks and seeks to protect himself from all sorts of adverse situations. For example, we have learned that because he does not need to sell higher, he effectively avoids to be at the mercy of the market.

Over the years, he has also worked to mitigate several other risks that negatively affect any investor. As a matter of fact, in Berkshire Hathaway, Buffett has devised an ingenious “machine” that provides him an upper hand on several facets of investing.

The set of structural advantages he holds when dealing with the “market” includes:

Avoid debt, prefer leverage from insurance float

To avoid dealing with debt obligations (like the need to service it or to roll it over) in market conditions that could eventually snowball against him, Buffett, for the most part, stays away from debt. Instead, he get leverage from Berkshire’s insurance float (under the terms that Berkshire itself underwrites and therefore “controls”)Avoid “timed” offerings

To avoid transactions deliberately timed by executives and investment bankers, Buffett tends to steer clear from new offerings (like IPOs) (sidenote: Buffett explains why an intelligent investor should avoid buying common stock at new issuances in his 1992 Annual Letter (see the section titled “Fixed-Income Securities”).) . He focus on buying stocks at open market, where he can choose the moment to actWhen purchasing entire businesses, buy only from sellers who want to sell

To avoid getting into auctions (and bidding wars) when buying private companies, Buffett avoids making the open move, he instead asks for every seller to open the negotiation with an offering pricePositive selection of sellers, stemming from Berkshire’s stellar reputation

To attract the right kind of sellers (and avoid adverse selection), he does not engage in unsolicited transactions. Instead, he has built Berkshire’s reputation as a safe harbor for private businesses. He does that by promoting Berkshire as a buyer that takes care of businesses for the long term (meaning, it “never” sells, it doesn’t touch on debt, etc)

In terms of buying entire private businesses, Buffett articulated the value proposition of Berkshire for prospective sellers as follows:

Berkshire offers to the business owner who wishes to sell: a permanent home, in which the company’s people and culture will be retained (though, occasionally, management changes will be needed). Beyond that, any business we acquire dramatically increases its financial strength and ability to grow. Its days of dealing with banks and Wall Street analysts are also forever ended.

Warren Buffett, 2014 Annual Letter

On the first structural advantage — avoid debt —, Buffett has been quoted having said: When you have debt, you have to wake up every morning and worry about what the world thinks of you

(sidenote: Quoted attributed to Warren Buffett by Mohnish Pabrai via Joe Ponzio (a).) .

His attitude towards debt is somewhat uncommon among market participants, so it’s worth digging deeper into it. Here’s a bit more color on debt and the way financial leverage is done at Berkshire as explained by the man himself:

We use debt sparingly. Many managers, it should be noted, will disagree with this policy, arguing that significant debt juices the returns for equity owners. And these more venturesome CEOs will be right most of the time. At rare and unpredictable intervals, however, credit vanishes and debt becomes financially fatal

We use debt sparingly. Many managers, it should be noted, will disagree with this policy, arguing that significant debt juices the returns for equity owners. And these more venturesome CEOs will be right most of the time.

At rare and unpredictable intervals, however, credit vanishes and debt becomes financially fatal. A Russian-roulette equation — usually win, occasionally die — may make financial sense for someone who gets a piece of a company’s upside but does not share in its downside. But that strategy would be madness for Berkshire. Rational people don’t risk what they have and need for what they don’t have and don’t need.

Beyond using debt and equity, Berkshire has benefitted in a major way from two less-common sources of corporate funding. The larger is the float I have described. So far, those funds, though they are recorded as a huge net liability on our balance sheet, have been of more utility to us than an equivalent amount of equity. That’s because they have usually been accompanied by underwriting earnings. In effect, we have been paid in most years for holding and using other people’s money.

As I have often done before, I will emphasize that this happy outcome is far from a sure thing: Mistakes in assessing insurance risks can be huge and can take many years to surface. (Think asbestos.) A major catastrophe that will dwarf hurricanes Katrina and Michael will occur — perhaps tomorrow, perhaps many decades from now. “The Big One” may come from a traditional source, such as a hurricane or earthquake, or it may be a total surprise involving, say, a cyber attack having disastrous consequences beyond anything insurers now contemplate. When such a mega-catastrophe strikes, we will get our share of the losses and they will be big — very big. Unlike many other insurers, however, we will be looking to add business the next day.

The final funding source — which again Berkshire possesses to an unusual degree — is deferred income taxes (sidenote: Here is a short article by QuickBooks with a few examples of deferred taxes.) . These are liabilities that we will eventually pay but that are meanwhile interest-free.

As I indicated earlier, about $14.7 billion of our $50.5 billion of deferred taxes arises from the unrealized gains in our equity holdings. These liabilities are accrued in our financial statements at the current 21% corporate tax rate but will be paid at the rates prevailing when our investments are sold. Between now and then, we in effect have an interest-free “loan” that allows us to have more money working for us in equities than would otherwise be the case.

A further $28.3 billion of deferred tax results from our being able to accelerate the depreciation of assets such as plant and equipment in calculating the tax we must currently pay. The front-ended savings in taxes that we record gradually reverse in future years. We regularly purchase additional assets, however. As long as the present tax law prevails, this source of funding should trend upward.

Warren Buffett, 2018 Annual Letter

To expand even further on float, Buffett has explained the dynamics of insurance float at Berkshire as follows:

Float has some similarities to bank deposits: cash flows in and out daily to insurers, with the total they hold changing very little

Berkshire now enjoys $138 billion of insurance “float” — funds that do not belong to us, but are nevertheless ours to deploy, whether in bonds, stocks or cash equivalents such as US Treasury bills.

Float has some similarities to bank deposits: cash flows in and out daily to insurers, with the total they hold changing very little.

The massive sum held by Berkshire is likely to remain near its present level for many years and, on a cumulative basis, has been costless to us. That happy result, of course, could change — but, over time, I like our odds.

Warren Buffett, 2020 Annual Letter

This collect-now, pay-later model leaves P/C [property and casualty insurance] companies holding large sums — money we call “float” — that will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, insurers get to invest this float for their own benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go, the amount of float an insurer holds usually remains fairly stable in relation to premium volume. Consequently, as our business grows, so does our float.

We may in time experience a decline in float. If so, the decline will be very gradual — at the outside no more than 3% in any year. The nature of our insurance contracts is such that we can never be subject to immediate or near-term demands for sums that are of significance to our cash resources. That structure is by design and is a key component in the unequaled financial strength of our insurance companies. That strength will never be compromised.

If our premiums exceed the total of our expenses and eventual losses, our insurance operation registers an underwriting profit that adds to the investment income the float produces. When such a profit is earned, we enjoy the use of free money — and, better yet, get paid for holding it.

Warren Buffett, 2018 Annual Letter

An important consequence of Buffett’s approach to risk minimization, especially with regard to debt, is that Berkshire has been able to move decisively when others simply can’t:

I guarantee you that people will do some exceptionally stupid things in equity markets sometime in the next 20 years. And then the question is, are we in a position to do something about that when that happens?

WB: We have some significant advantages in buying businesses over time. We would be the preferred purchaser, I think, for a reasonable number of private companies and public companies as well.

Our checks clear. We will always have the money. People know that when we make a deal, it will get done, and it will get done as fast as anybody can do it. It won’t be subject to any kind of second thoughts or financing difficulties. And we bought, as you know, we bought Johns Manville because the other group had financing difficulties.

People know they will get to run their businesses as they’ve run them before, if they care about that, and a lot of people do. Others don’t.

We have an ownership structure that is probably more stable than any company our size, or anywhere near our size, in the country. And that’s attractive to people.

And we are under no pressure to do anything dumb. You know, if we do things dumb, it’s because we do things dumb. It’s not because anybody’s making us do it.

So those are significant advantages. And the disadvantage, the biggest disadvantage we have is size. I mean, it is harder to double the market value of a $100 billion company than a $1 billion company, using what we have in our arsenal.

CM: Yeah. This is not a hog heaven period for Berkshire. The investment game is getting more and more competitive. And I see no sign that that is going to change.

WB: But people will do stupid things in the future. There’s no question. I mean, I will guarantee you sometime in the next 20 years that people will do some exceptionally stupid things in equity markets.

And then the question is, are we in a position to do something about that when that happens? But we do continue to prefer to buy businesses, though. That’s what we really enjoy.

Buffett & Munger, 2001 Annual Meeting

Ultimately, what is the net result of having less exposure to risks?

Having less “things that could go wrong” means that you have actually increased your chances of having “things that could well.”

But that’s not all with Buffett.

Be disciplined with price and mind all alternatives

When it comes to actually pulling the trigger and making an investment, Buffett does two additional things very well.

Firstly, Buffett treats every investment as a capital allocation decision that bears opportunity cost. Before making any investment Buffett always considers all competing alternatives, including doing nothing and simply holding cash until something more certain appears:

It’s crazy not to compare it to things that you’re already very certain of

CM: I would argue that one filter that’s useful in investing is the simple idea of opportunity cost. If you have one opportunity that you already have available in large quantity and you like it better than 98% of the other things you see, you can just screen out the other 98% because you already know something better.

WB: If somebody shows us a business, the first thing goes through our head is: Would we rather own this business or more Coca-Cola? Would we rather own it than more Gillette? It’s crazy not to compare it to things that you’re [already] very certain of. There are very few businesses that you will find that we’re a certain of the future about as company such as that. And therefore we will want [new] companies where the certainty gets close to that.

CM: With this attitude you get a concentrated portfolio, which we don’t mind. This practice of ours, which is so simple, is not widely copied. I do not know why.

Buffett & Munger, 1997 Annual Meeting

Moreover, because Berkshire is a diversified conglomerate that invests both in the private and public markets, he has a much broader universe to pick from (vs most other insurers, vs most other professional money managers, etc).

And secondly and crucially, he is particularly disciplined on the price he pays for anything.

We’ve already learned that he only buys when he is highly confident that the opportunity at hand meets his 10-year predictability criteria. The discipline on price is an additional layer. It is yet another act to mitigate the risk of losing money.

To reduce his chances of losing money due to predictions that might turn out to be too optimistic, Buffett seeks to buy only when there is a significant difference between his estimate of an asset’s intrinsic value vs its current selling price.

Whenever he discusses this point, Buffett often refers to Ben Graham’s concept of margin of safety. While on the subject, he also draws an analogy between the stock market and baseball:

You only swing when you are really confident things at your sweet spot

WB: I was genetically blessed with a certain wiring that’s very useful in a highly developed market system, where there’s lots of chips on the table. I happened to be good at that game.

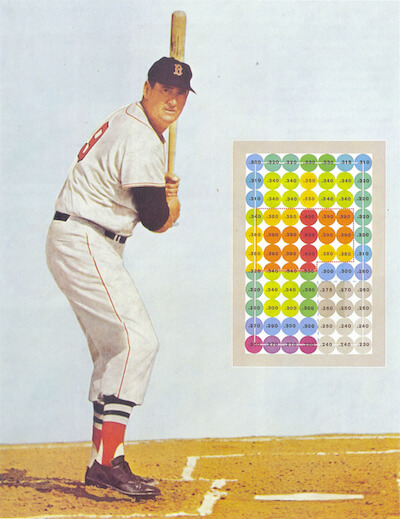

Ted Williams wrote a book called The Science of Hitting. In that, he had a picture of himself at bat, and the strike zone broken into, I think, 77 squares. He said that if he waited for the pitch that was really in the sweet spot (sidenote: Look for the red and orange circles in the image below. Click (or tap) on the image to zoom in.) , he would bat 0.400. And if he had to swing at something on the lower corner, he would probably bat 0.235.

In investing, I’m in a “no-called strike” business, which is the best business you can be. I can look at a thousand different companies, and I don’t have to be right on every one of them. Or even 50 of them. So I can pick the ball I want to hit.

The trick in investing is just to sit there and watch pitch after pitch go by — wait for the one right in your sweet spot.

As for people yelling “Swing, you bump,” simply ignore them. There’s a temptation for people to act far too frequently in stocks simply because they’re so liquid.

Warren Buffett, Becoming Warren Buffett (2017 Documentary)

In summary

Require assets to pay for themselves. Try to predict the future only in specific circumstances — ones that seem sufficiently stable over time. To avoid what could go wrong, design structural advantages and be disciplined with price. Finally, before deploying any capital, always consider the several competing alternatives.

And there you have it, a distillation of Warren Buffett’s investing system.

This article is not investment advice. It is for educational purposes only.